Four out of five software teams now use artificial intelligence in their testing workflows. Vendors promise self-healing scripts, autonomous test generation, and—inevitably—the obsolescence of manual testers. Yet by the measures that matter to engineering leaders, remarkably little has changed. Test maintenance still consumes a substantial share of automation budgets. Flaky tests still derail releases. The QA headcount that was supposed to shrink has, in many organisations, quietly grown.

The artificial intelligence revolution in software testing is real. The productivity revolution is not.

The adoption paradox

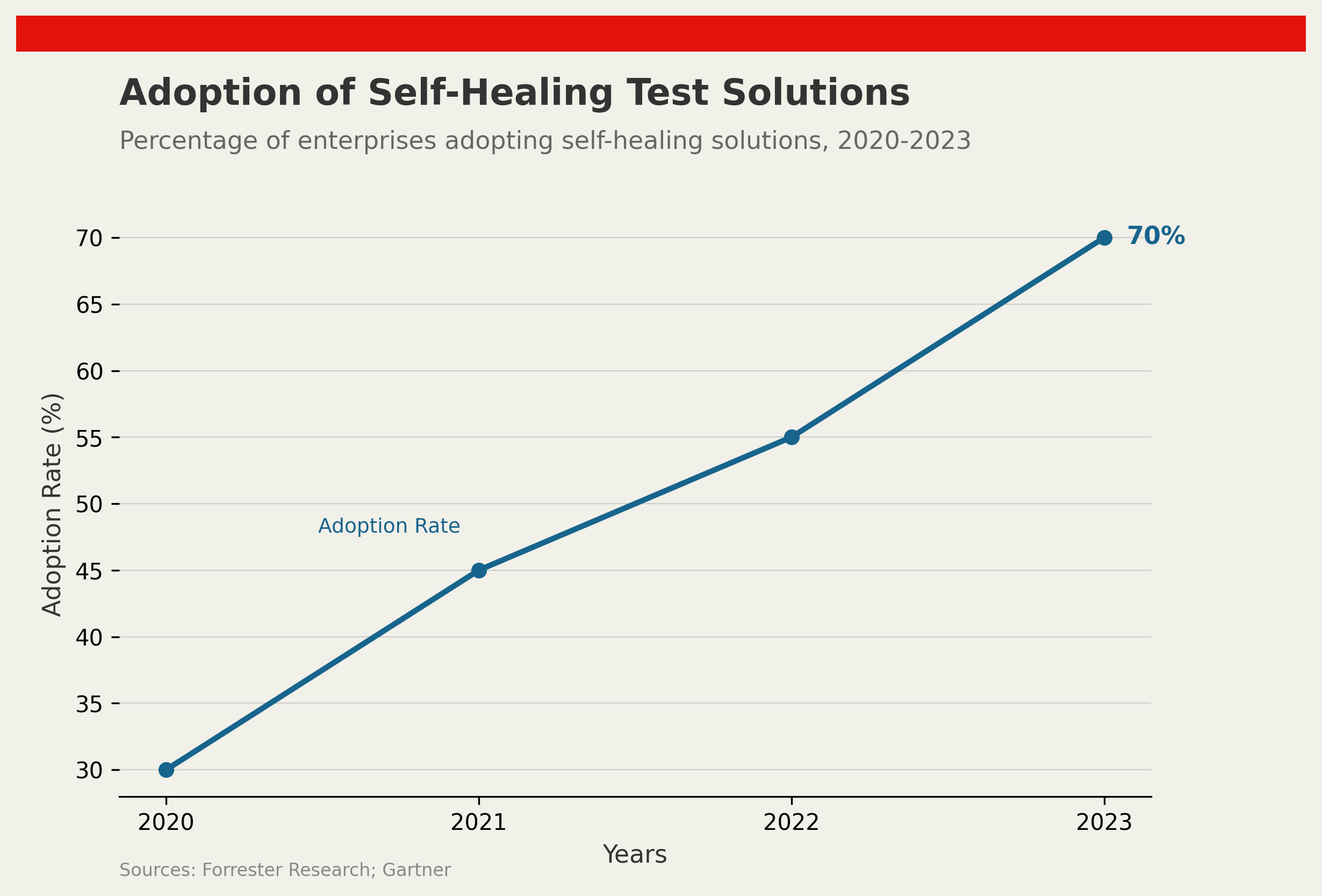

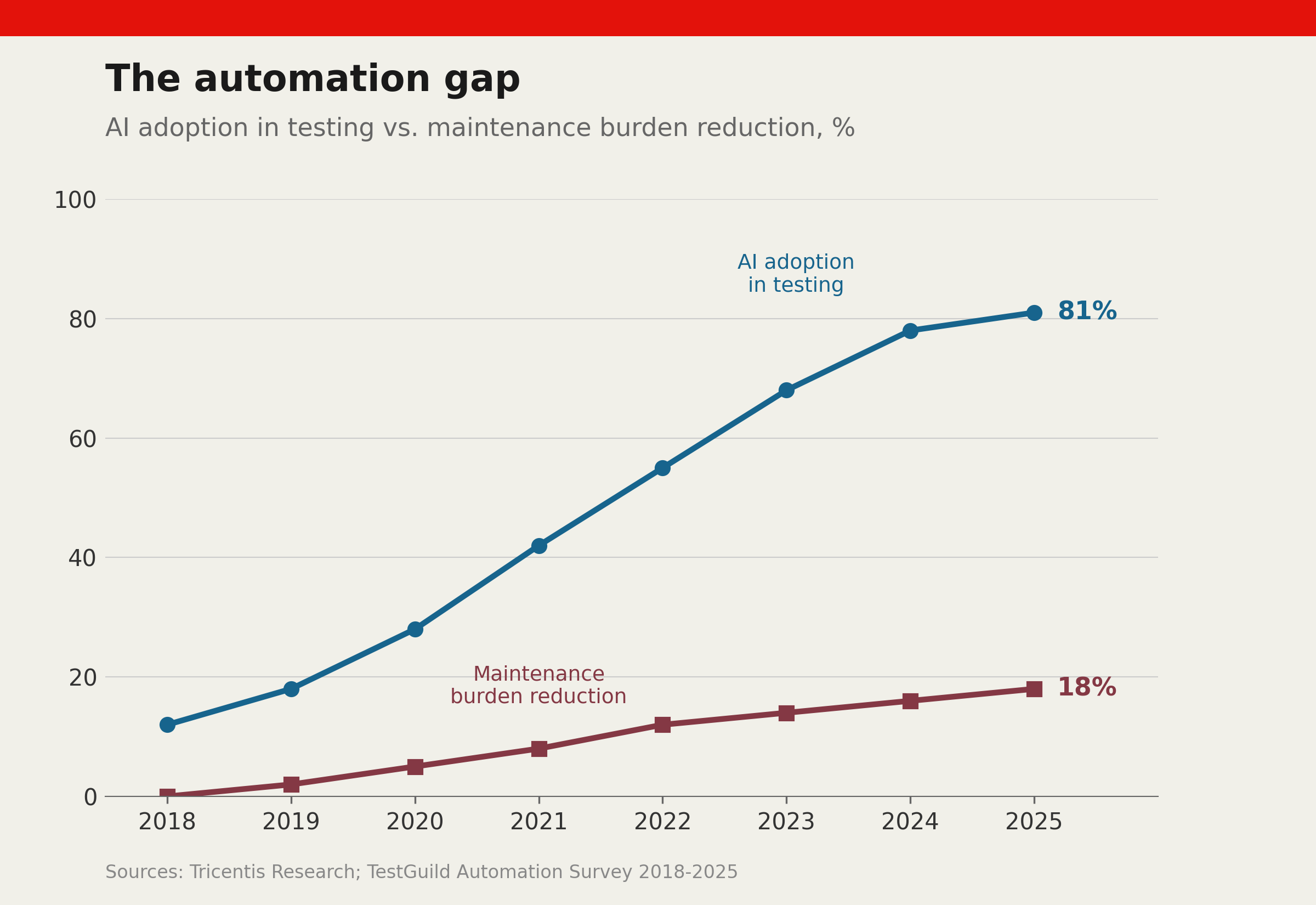

The numbers on AI adoption are striking. According to Tricentis research, 80% of software teams will use AI-assisted testing tools by the end of 2025. A separate survey by TestGuild found that DevOps adoption—a proxy for modern testing practices—jumped from 17% of teams in 2022 to 52% in 2024. Generative AI, the technology behind tools like GitHub Copilot, is now used by 61% of organisations for code generation and test scripting.

As the chart shows, these adoption curves look like hockey sticks. The maintenance burden has barely budged. When TestGuild surveyed practitioners about their top challenges, test maintenance and flaky tests ranked first and second—the same positions they held in 2019, before the current AI wave began. Self-healing capabilities, the feature most loudly trumpeted by vendors, appear to reduce maintenance effort modestly in practice, far short of the dramatic reductions promised in product demonstrations.

The pattern is familiar to anyone who has watched previous waves of testing automation. Selenium promised to eliminate manual regression testing; it created a new category of maintenance burden instead. Codeless tools promised to let business analysts write tests; they shifted the bottleneck from creation to debugging. Each generation of tooling solves one problem while quietly creating another.

Where the value hides

This is not to say AI delivers nothing. The productivity gains are real—they are simply not where the marketing suggests.

The clearest wins come from test generation, not test maintenance. Engineers report that AI assistants can produce a first draft of unit tests in a fraction of the time required to write them manually. These generated tests require significant review and refinement, however. They optimise for coverage metrics rather than meaningful assertions. One engineering director at a fintech firm describes AI-generated tests as “very good at finding the easy bugs we would have caught anyway, and very bad at the subtle ones that actually ship to production.”

The second area of genuine value is triage. Modern AI tools excel at clustering failures, identifying root causes, and prioritising which flaky tests to fix first. This is unglamorous work that previously consumed hours of engineering time. Automating it delivers measurable returns—though not the transformative kind that justifies premium pricing.

The third benefit is accessibility. Low-code and no-code testing platforms, now augmented with natural language interfaces, have genuinely lowered the barrier to test creation. Business analysts and product managers can contribute test cases in ways that were previously impossible. Whether this proves a net positive depends on who maintains those tests six months later.

The maintenance trap

The fundamental problem is architectural, not technological. AI tools optimise for the moment of test creation. The cost of testing, however, accumulates over time. A test that takes five minutes to generate with AI and runs successfully for three months still requires human judgment when it starts failing. Someone must determine whether the failure indicates a genuine bug, a flaky dependency, an environment issue, or a test that no longer reflects valid requirements.

“Self-healing capabilities address only the narrowest slice of this problem: locator changes in user interface tests. When a button’s position shifts or a CSS class name changes, AI can often detect and fix the broken selector automatically. This is useful but marginal. It does nothing for the test that fails because an upstream API changed its contract, or because a race condition surfaces under load, or because the business logic it validates is no longer correct.”

The vendors know this. Their roadmaps increasingly emphasise “agentic AI”—autonomous systems that can not only fix tests but decide which tests to run, when to run them, and whether a failure matters. The vision is compelling. The gap between vision and production-ready capability remains measured in years, not months.

The quiet revolution

“The most significant change may not be AI itself but the organisational shifts it has accelerated. The companies extracting real value from AI-assisted testing share a common pattern: they have dissolved the boundary between quality engineering and software development. QE specialists are embedded in platform teams rather than siloed in a separate department. Testing is a shared responsibility rather than a handoff.”

In these organisations, AI tools amplify human judgment rather than replacing it. Engineers use AI to generate test scaffolding, then apply domain knowledge to refine assertions. They use AI-powered triage to focus attention, not to avoid thinking. The productivity gains are genuine but unglamorous—15% here, 20% there—compounding over time rather than arriving in a single dramatic leap.

This is, perhaps, the lesson of every automation wave. The technology that promises to eliminate human work instead changes its nature. The organisations that thrive are those that adapt their structures to match. The tools matter less than how they are wielded.

The pragmatic path

The shrewdest quality engineering leaders are budgeting for maintenance as if their AI tools did not exist. Any reduction, they reason, is upside rather than baseline. This defensive posture may seem pessimistic. Given the track record of automation promises, it is merely prudent.

They are also measuring what matters. AI tools generate impressive coverage numbers. Coverage is a vanity metric. Defect escape rate—the percentage of bugs that reach production despite the test suite—tells a truer story. So does mean time to detect failures in CI pipelines, and the ratio of test maintenance hours to feature development hours. These metrics reveal whether an AI investment is paying off or merely generating activity.

The AI revolution in software testing is genuine. It is also, for now, incremental. The teams that thrive will be those that harness the technology for what it does well—acceleration, triage, accessibility—while remaining sceptical of what it claims to do. In testing, as in much else, the most expensive promises are those that sound too good to be true.